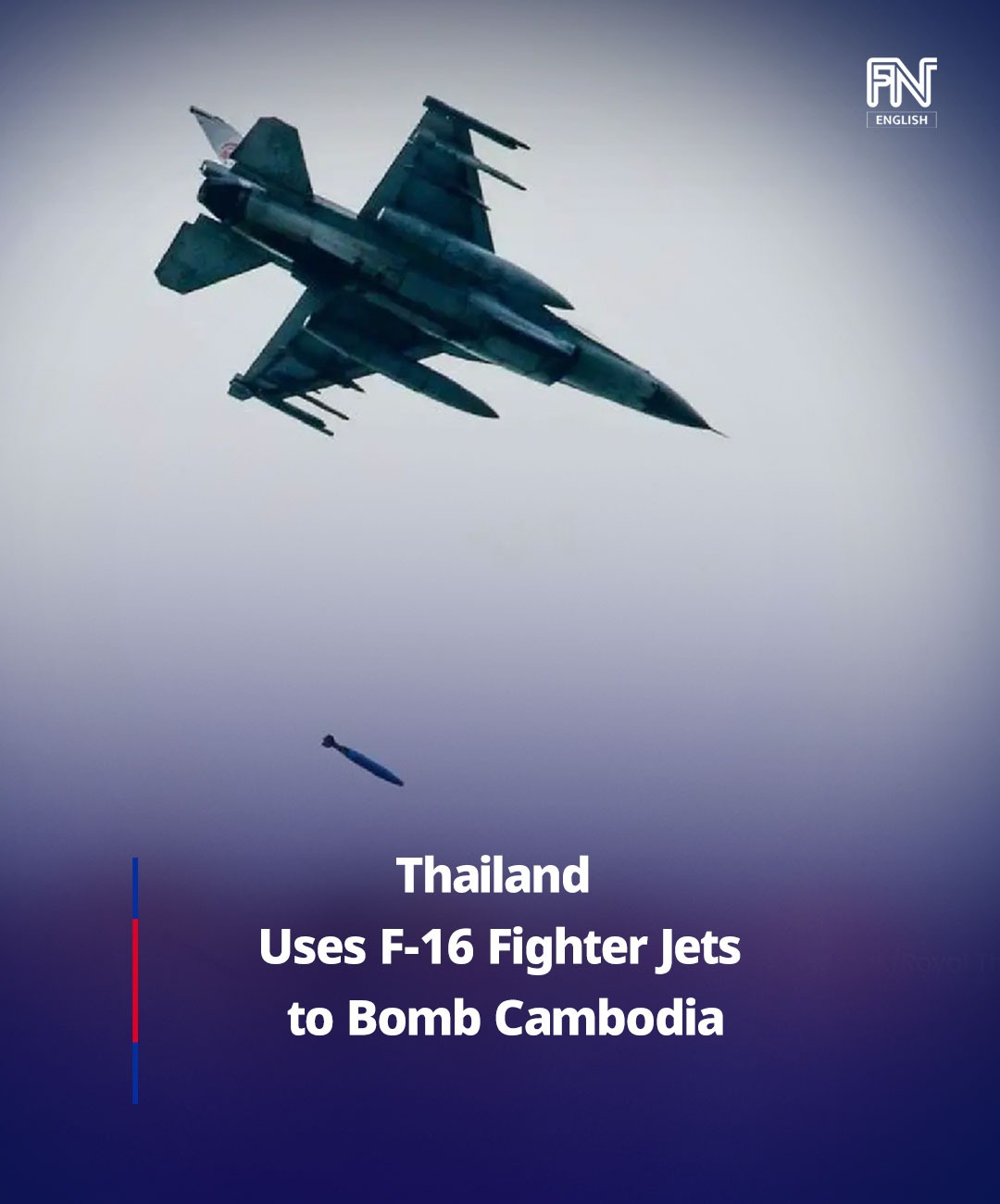

Two weeks ago I published an essay on the Cambodia-Thailand conflict and how I could not be silent about it as a foreigner living in Phnom Penh.

It was liked by the thousands and shared by the tens-of-thousands. People even copied and pasted my words to appear under their names. It was shared by very important people too, by Cambodia’s former Minister of Information, by the former editor-in-chief of the Kampuchea newspaper, by senior figures in the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) and even recommended online by the Senior Advisor to the King of Cambodia. Even the government-aligned media platform FreshNews published my lines as their Editor’s Pick.

I was honored. I was also acutely aware of what it meant.

Because here’s the paradox of being a foreigner with a platform on Cambodian national matters (with my own little Facebook account, let’s not exaggerate): I’m honored to be read, but I’m painfully aware of the complications. The truth is, we foreign residents writing things online perform a fantastic method of self-censorship. We seriously can’t say everything we want to say or point fingers at the elite and name names with absolute responsibility… no, not about anything. It would make life difficult. An interview with uniforms. A visa that doesn’t get renewed when the time comes. Consequences that accumulate quietly.

My essay went viral not because it was radical, but because it offered something desperately scarce in the current discourse: balance. Nuance. An attempt at understanding rather than the tribal cheerleading that I see around me everywhere. And that itself felt revolutionary in a media landscape drowning in nationalistic manure. Yes, I can write that, though.

So yes, I self-censor. I even lost a few Facebook friends who called me a narcissistic idiot for not just ffs mentioning the responsible people by their names. Yes, there are invisible lines I won’t cross because I’d like to stay in this country I’ve chosen to call home. Yes, there are things I think but cannot write, names I know but will not publish.

But “measured speech” from somebody who wants to understand the country he is a welcomed GUEST in, who wishes to understand its geopolitics with its neighbors and desires far more balanced journalism than the current nationalistic propaganda published online, that is still worth so much to me.

I won’t ever use the internet to lecture Cambodia. I’m here to try to understand it. To learn from it. To contribute what I can from where I stand. Because the alternative – silence or propaganda – serves absolutely nobody. Cambodia deserves better. It deserves analysis that doesn’t bend to tribalism. It deserves voices that care enough to “speak carefully” rather than carelessly or not at all.

I’ll keep writing. Not everything I think, but everything I can responsibly say. Because even partial honesty, even imperfect analysis, is better than the binary shouting match that dominates the discourse these days. I’m a foreigner, yes, but one who has chosen to be here, to stay here, to understand this place and contribute what measured truth I’m able to give.

That’s the obligation I feel. That’s the responsibility that comes with being read, heard and shared. And I’ll carry it as carefully as I can.

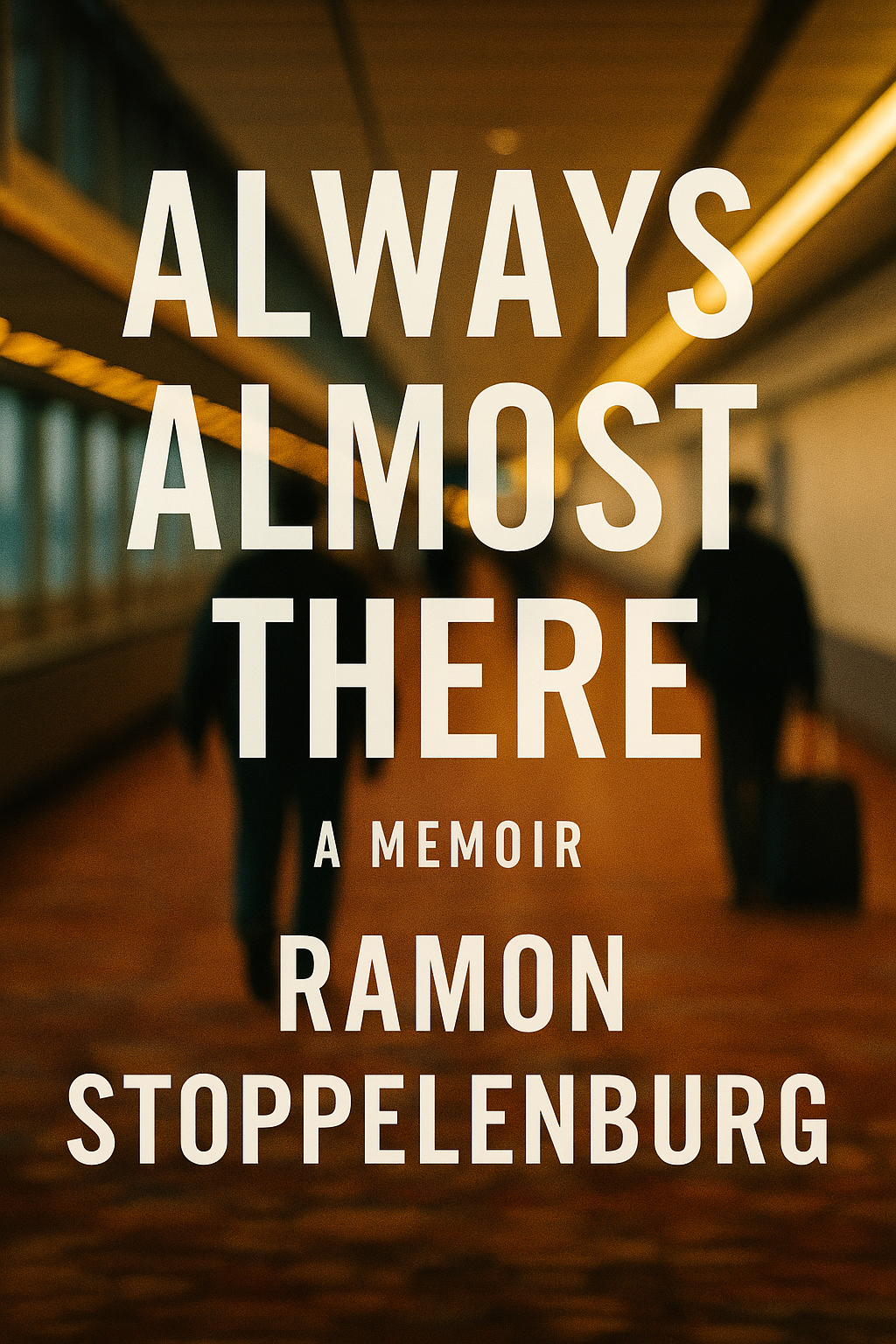

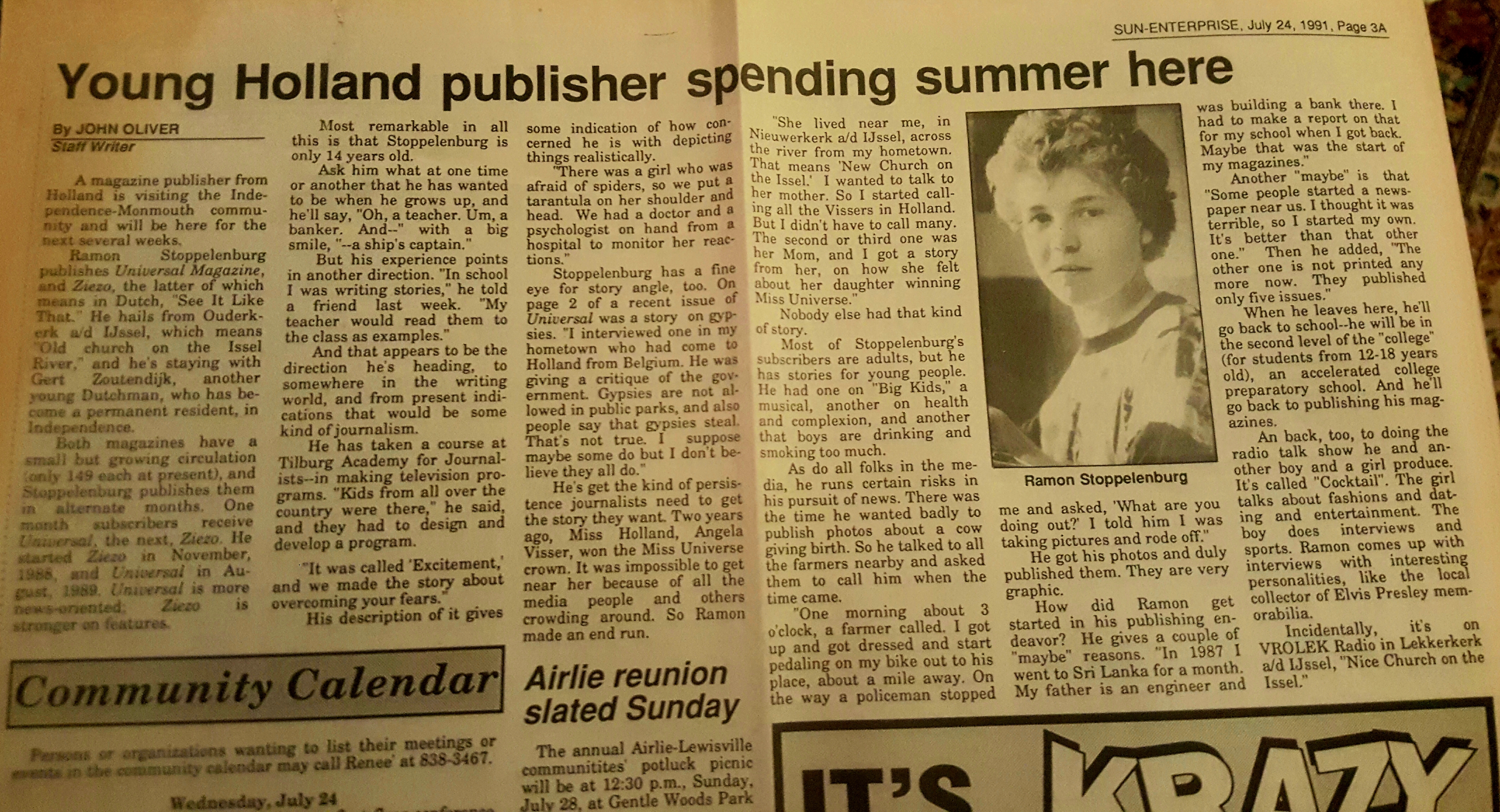

Ramon Stoppelenburg

I wrote an unsalted opinion on my experiences with the Portuguese kitchen, “

I wrote an unsalted opinion on my experiences with the Portuguese kitchen, “

Mother of Georgia symbolizes the Georgian national character: in her left hand she holds a bowl of wine to greet those who come as friends, and in her right hand is a sword for those who come as enemies.

Mother of Georgia symbolizes the Georgian national character: in her left hand she holds a bowl of wine to greet those who come as friends, and in her right hand is a sword for those who come as enemies.

I found a $400pm 2-bedroom apartment there with ease and only had to find this business location to set out my dreams and show the people here what a good life with great movies is.

I found a $400pm 2-bedroom apartment there with ease and only had to find this business location to set out my dreams and show the people here what a good life with great movies is. In the meantime I started a side hustle. I discovered nobody was selling cupcakes in this city and that opened a chance for me to jump in and see how it goes if I would be that somebody. I even added alcohol to my cakes and went commercial with my Shotcakes. Shotcakes received raving reviews, had enthusiastic crowds and was a big hit at parties. But I would have to sell 12 cakes (one box) per day to even get even on my rent and very slowly I realized that was not actually happening. Perhaps if I threw in a giant marketing campaign to get the entire city involved, but I had no budget for that.

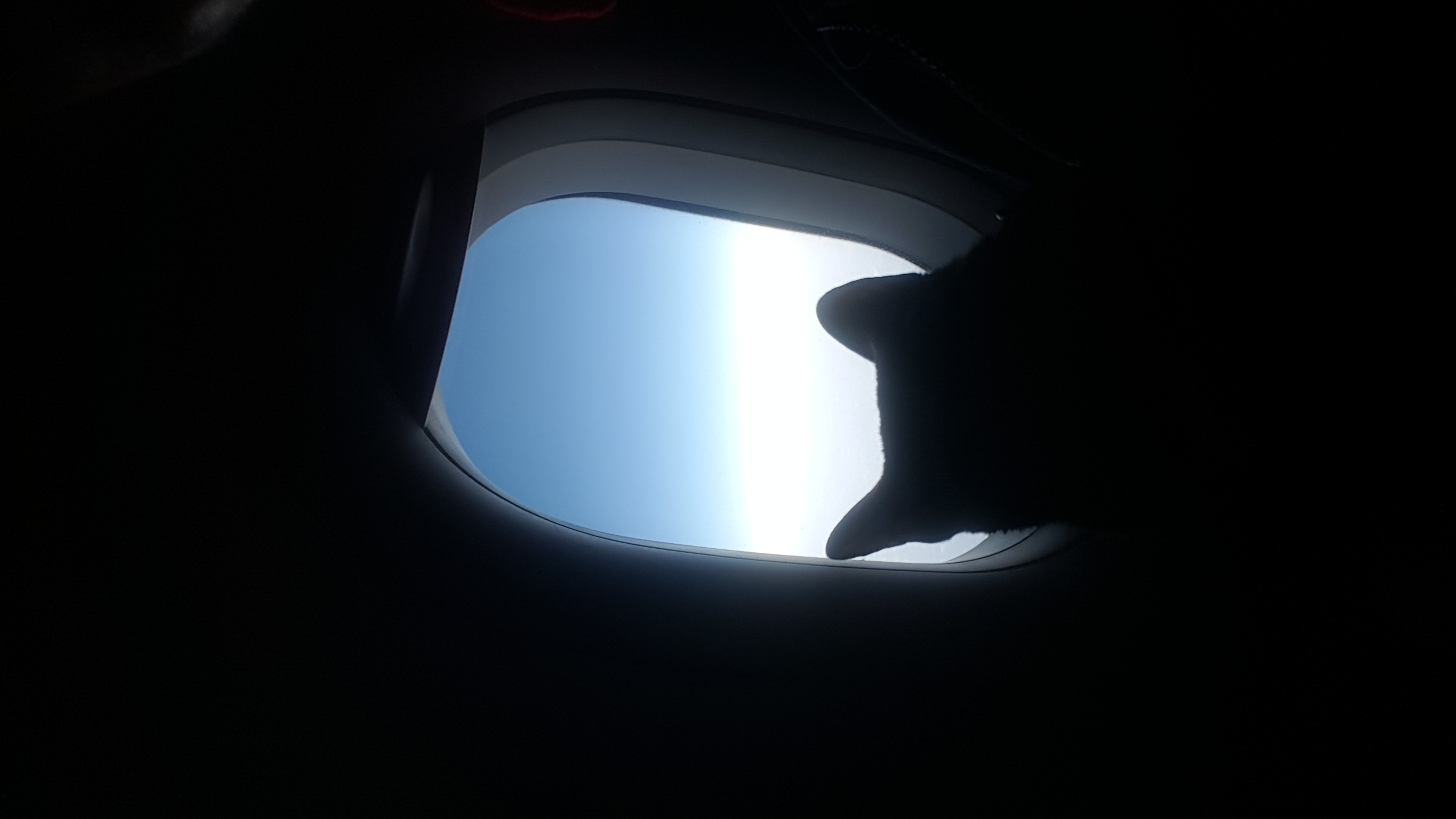

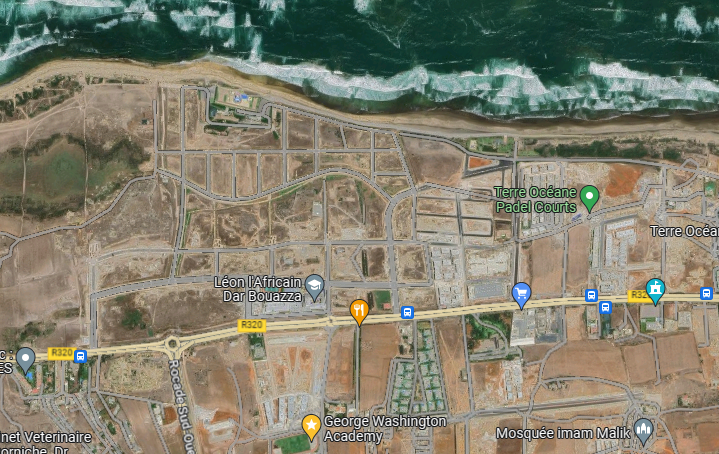

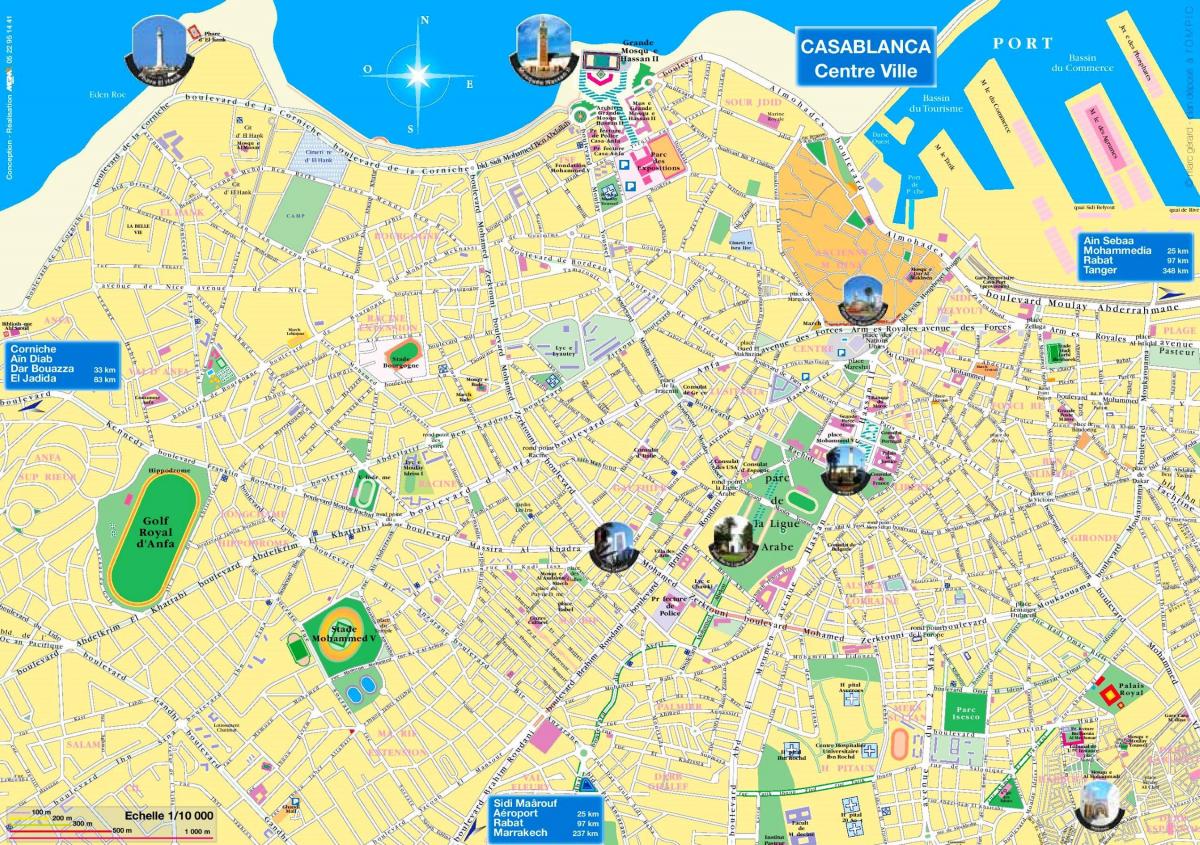

In the meantime I started a side hustle. I discovered nobody was selling cupcakes in this city and that opened a chance for me to jump in and see how it goes if I would be that somebody. I even added alcohol to my cakes and went commercial with my Shotcakes. Shotcakes received raving reviews, had enthusiastic crowds and was a big hit at parties. But I would have to sell 12 cakes (one box) per day to even get even on my rent and very slowly I realized that was not actually happening. Perhaps if I threw in a giant marketing campaign to get the entire city involved, but I had no budget for that. So that’s where I ended up. In Casablanca, Morocco. It took a while though, because when I was ready to leave Georgia in December last year, Morocco closed its borders due to the omicron fears and I had to stay put and simply get through every day in the most possible boring ways. When Morocco announced to open again from February 7, I booked the flights out of Georgia with whatever funds my credit card allowed me. Together with Shady, my weird Cambodian cat.

So that’s where I ended up. In Casablanca, Morocco. It took a while though, because when I was ready to leave Georgia in December last year, Morocco closed its borders due to the omicron fears and I had to stay put and simply get through every day in the most possible boring ways. When Morocco announced to open again from February 7, I booked the flights out of Georgia with whatever funds my credit card allowed me. Together with Shady, my weird Cambodian cat.

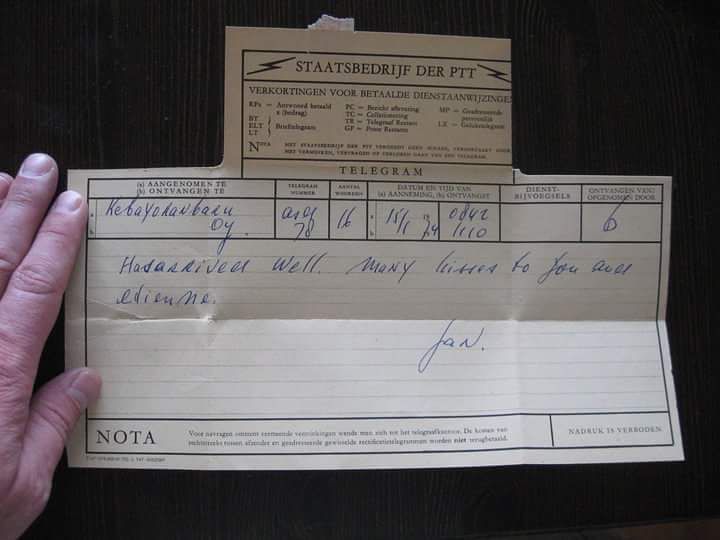

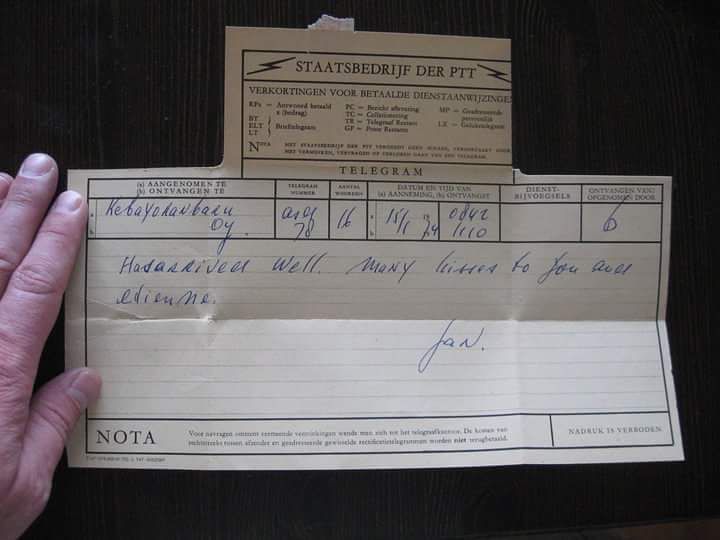

On New Year’s day I arrived by train from Rotterdam in the small city of

On New Year’s day I arrived by train from Rotterdam in the small city of

We ate French

We ate French